As I have argued before, critical history, in particular of the kind that embraces dialectical historical materialism, is considered dangerous to the establishment because it usually intervenes with its ability to engage politically as a means to pursue its own interests while presenting these as universal. Establishment politics – of whatever ideological persuasion – prefer identity thinking and mythologies. This is because these are not based on concrete experiences and can thereby deploy arbitrary symbolic violence without many real obstacles.

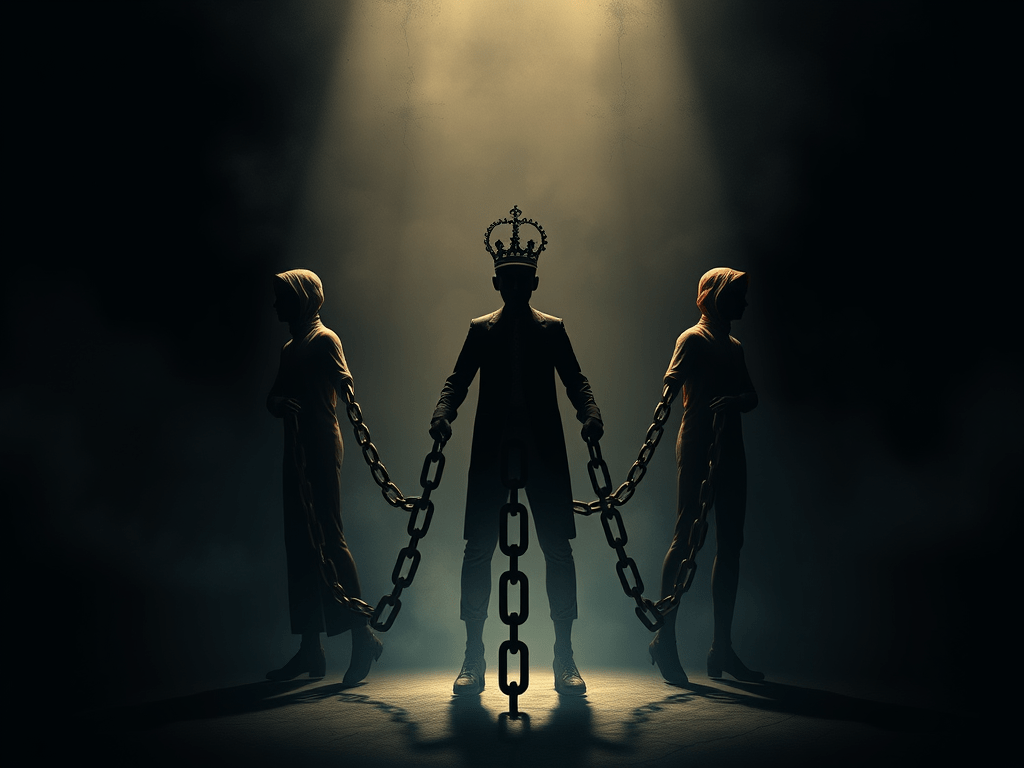

One very effective way to problematize identity thinking is to focus on associations in terms of energy and motivation. By distinguishing between the economic wealth-motive, the political power-motive and the libidinal appeal-motive (or admiration-motive), overly-reductionist accounts of these associations can be prevented, while focusing on their interconnections highlights the importance of understanding sociality as a libidinal-political-economy. This is a triad that one can always identify when answering the question: what do powerful men want?

The libidinal-political-economy of the establishment is rooted in the materiality of the estate, even if those who benefit most from this relationship are also those that seek to mystify and mythologize it. What needs to be stressed however, is that this shows that any false dichotomy between “systemic” and “historical” (contingent) understandings of this relationship has to be avoided. It is not a contradiction, for example, to point out that the specific systemic traits of capitalism, imperialism and patriarchy – and the fact that all three are necessarily intertwined – are also linked to concrete figurations of wealth, power and desire, that are typically linked to actually existing individuals (mostly men) who have names, addresses and birth certificates.

It is now possible to draw a parallel between Jason W. Moore’s world-historical analysis of the birth and evolution of the triad of capitalism, imperialism and patriarchy with the inter-psychological analysis of mimetic desires as rooted in a libidinal-political-economy of figurations. This goes beyond the simple pairing of three words: (1) capitalism and the wealth-motive (economy); (2) imperialism and the power-motive (political); and (3) patriarchy and the appeal motive (libidinal). We have to understand that these three items are BOTH necessarily interconnected AND contingently individuated (an idea that one can attribute to Hegel and more recently Quentin Meillassoux).

For this, we need to understand that what connects the estate and the establishment is an assemblage (or web) of practices, among which practices of extraction and abstraction. The work of establishment takes place on an estate, it draws everything it has form the estate: raw materials, labour, energy, food, care (see Patel and Moore, 2018) but it also organizes these practices of extraction and abstraction, for example through the deployment of institutions which function as mediators and regulators of production and reproduction.

One of the interesting insights of Alfred Sohn-Rethels work on Intellectual and Manual Labour is that he refuses to disconnect them as completely separate realms and thereby avoids the spectatorial materialist fallacy of the likes of Feuerbach and other bourgeois ideologues, which Marx and Engels so eloquently exposed in the German Ideology. It is a bit surprising that the core of his thesis, that modern philosophy could only come into being through the real abstraction associated with the emergence of capitalism, has not had a bigger influence on sociology, since it could have been used to strengthen this discipline’s scientific appeal as being more than just a handmaiden of the modern establishment and its administrative apparatus.

However, if we approach the thesis in the context of a more pragmatic, dialectical historical materialism, it can be used to explain the epistemic shifts regarding labour, life and language, which are at the core of Foucault’s archaeological analysis in Les Mots et les Choses, but which without taking real abstraction into account, can only be understood as coincidental, symptomatic cross- fertilizations of thought. The matrix of wealth, power and appeal can of course be mapped onto the epistemic shifts in the studies of labour, life and language and it would not be very difficult to understand that they point towards similar modalities. It is almost as if the triad could be endlessly reproduced, which is exactly the point that Sohn-Rethel’s thesis addresses: there is an innate logic to the mode of abstraction that governs the western metaphysical tradition that is part of the singular reality that philosophers usually refer to as “the world”

As inhabitants of the modern world, we all know about extraction. Since the very beginnings of agriculture, human beings have been using the ability of particular plants, such as wheat and rice, to extract water and minerals from the earth, C02 and Oxygen from the air, light from the sun, in order to produce food. They have also learned to extract wood from trees and burn it for heat or turn it into lumber for shelter, fencing and tools, to extend control over their environments. They have learnt that animal skins can be used to make clothing, clay can be used to make pottery, fermentation can be used to make water drinkable as beer or wine and water can be boiled to make tea. The discovered that the earth contains various metals with which they could make weapons and durable materials that papyrus can be used to make paper and that excrement can be used as fertilizers. Much later, humans have learnt to extract more energy from “dead life” in the form of fossil fuels, which sparked the industrial revolution.

However, whereas this may sound like a brief introduction to the Anthropocene, it should be obvious by now, that completely absent from this story of “human civilization” is the question “why?”. For what reasons did humans come to cultivate the earth and control their environment? Evolutionists may think they know the answer, but they can only do so teleologically, using the notions of random variation and natural selection to “explain” the progressive (and increasingly destructive) impact of humans onto their environment. Historians have done a better job in this respect, by focusing on conflicts, being able to explain why the “best” techniques and strategies to extract raw materials and energy and produce food, did not always succeed.

What is clear, however is that both functionalist and historicist explanations of the coming into being of the so-called Anthropocene are inadequate without taking the political into account. From the very beginnings of agriculture, labour and technology were not merely neutral forces, represented with the idea of “man” versus “nature”; they were contested, political practices. For example, if one fails to understand slave labour as political, then why is the so-called modern history of human civilization never written from the perspective of slave labour? In Eurocentric accounts of human civilization, slaves were never fully human, but always part of the nature that needed to be conquered. The same goes for technology, which is both inside and outside of nature, both human and nonhuman at the same time. This is not simply a category error, but emblematic of the problem of any anthropocentric non-dialectical reading of history.

Leave a comment